|

|

||||||

|

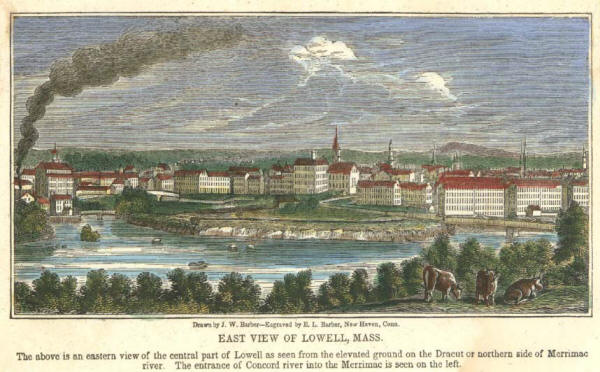

History: Cultural Views of the River Contrasting Views With the rise of industrial capitalism and the transformation of the 19th century landscape in increasingly urban areas like Lowell, Americans expressed a range of views about society’s relationship to the rapidly changing “natural world.” Many spoke admiringly of the engineering feats that dammed rivers for manufacturing and turned fields, woodlands, and rural villages into cities. And many proclaimed technological and commercial developments to be the fruits of a virtuous, producer-oriented republic, equating material advances with the “progress” of human civilization. Others, however, warned of loss and separation of humans from nature by pecuniary interests and greed, resulting in a mutual degradation of nature and the human spirit. Still others sought to “soften” the ill-effects of industry on the landscape by introducing parks, promenades, and even pastoral cemeteries in the nation’s burgeoning cities.

Henry David Thoreau, Naturalist and

Social Critic

James W. Meader, Mechanic from

Newburyport

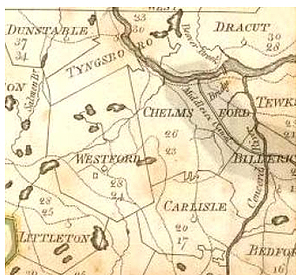

The River’s Appearance “Compared to other tributaries of the Merrimack, [the Concord] appears to have been properly named Musketaquid, or Meadow River, by the Indians. For the most part it creeps through broad meadows, adorned with scattered oaks, where the cranberry is found in abundance, covering the ground like a mossbed.” Henry David Thoreau “The Concord is 50 miles in extreme length and … it has more the appearance and characteristics of a lake … Its immobility is unparalleled by any other tributary to the Merrimack; it is dark, sullen, and sluggish, making out into considerable lagoons in places, producing the plants, flowers, fish, and reptiles of the most stagnant and miry ponds, and nothing more.” James W. Meader

Life in the River “Salmon, Shad, and Alewives were formerly abundant here, and taken in weirs by the Indians, who taught this method to the whites, by whom they were used as food and as manure, until the dam, and afterward the canal at Billerica, and the factories at Lowell, put an end their migrations hitherward.” Henry David Thoreau “[T]he country through which it

passes being so remarkably level that its waters are sullen,

sluggish, and slimy, making out through numerous depressions in the

soil in extensive marshes and lagoons, foul with rank water grasses

and filthy reptiles, the haunt and fishing ground of the majestic

bittern, … the black tortoise, the spotted fresh-water terrapin, the

great water adder, and the hordes of disgusting water-bred reptiles,

common to stagnant pools; its redeeming features being the fine

farms and broad green fertile intervals which border it, and the

‘milky way’ starred with the great white water lily of midsummer,

which in unequal beauty and fragrance floats gracefully upon its

tranquil surface.”

The Dam at Billerica “Armed with no sword, no electric shock, but mere Shad, armed only with innocence and a just cause … I for one am with thee, and who knows what may avail a crow-bar against that Billerica dam?” Away with the superficial and selfish phil-anthropy of men,— who knows what admirable virtue of fishes may be below low water-mark, bearing up against a hard destiny, not admired by the fellow creature who alone can appreciate it! Who hears the fishes when they cry?” Henry David Thoreau “The falls on the Concord River at Billerica have long been used for mechanical and manufacturing purposes and were an important element in the prosperity of that section more than a century before ground was broken for manufacturing purposes at Lowell….[The falls and dam symbolize] “not only the necessity, but the grandeur of a reformation, which, by earnest, vigorous works, testifies to an ultimate appreciation of the duties, objects, and obligations imposed by the very fact of the creation of capacity and inherent power” James W. Meader Nature and Works of Man “This canal, which is the oldest in the country, and has even an antique look beside the more modern railroad, is fed by the Concord, so that we were still floating on familiar waters. [Yet] it is so much water that the river lets for the advantage of commerce. There appeared to be some want of harmony in its scenery, since it was not of equal date with the woods and meadows through which it is led, and we missed the conciliatory influence of time on land and water. But in the lapse of ages, Nature will recover and indemnify herself, and eventually plant fit shrubs and flowers along its borders. Thus all works pass directly out of the hands of the architect [and] into the hands of Nature.” Henry David Thoreau “The deep tinge of romance surrounding this stream in its native condition has not faded or diminished, but is, rather, intensified by the peculiarities of the men and the circumstances connected with the inauguration and prosecution of improvements around its splendid falls.” James W. Meader

Personifying the River “There is an inward voice that in

the stream James Meader compared the stretch of the Concord River, below the dam, to a person, perhaps like himself, who seeks some larger purpose in life: “If, in some sense, a river is the

type of human life, this particular stream may be cited as

symbolizing the actual career of many individuals known to those who

may give the comparison a little reflection. How many are there who

start off on a journey of life like this stream,—useless, lifeless,

and aimless, instead of becoming a wheel, a lever, an axle, a

something in that complicated machine called society. Thus it

is with individual idleness disfiguring the course of life with

waste places, while the sedges, rank water weeds, and ugly, filthy

reptiles represent the vices, little and great, the fungi bred by

indolence,—a parasitic growth. At Lowell [the Concord], like the

man who awakens to a realizing sense of his duties, obligations, and

responsibilities at the eleventh hour, throws off the lethargy that

has held it so long in chains, dashing over two miles of picturesque

and powerful falls …seems to seek, and with entire success, to

compensate for its former vagrant life and finally throws itself

with alacrity into the Merrimack, leaving no space between the

termination of its beneficent labors and its final doom.”

|