|

|

||||||

|

History: River as Sink and Sewer Growing Pollution Problems in the Nineteenth Century The rise of manufacturing along the Concord River in 19th-century Lowell was accompanied by growing amounts of factory pollutants dumped into the stream and its tributaries. The most conspicuous wastes originated from woolen mills, dye works, and tanneries. By the 1870s and 1880s, however, a number of other industrial concerns, including a cartridge factory, boiler shops, a lampblack works, and other smaller manufacturing companies also polluted the watershed with a range of harmful effluents. By the end of the 1880s, the water quality of the Concord River had deteriorated to such an extent that the city’s board of health considered it a “sewer basin,” and yet virtually nothing was done to curb industrial polluters.[1]

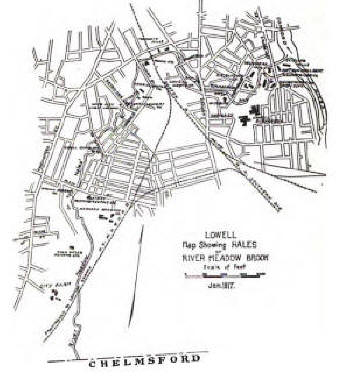

Industrial Pollution Among the primary contributors to the growing pollution problem of the Concord River in Lowell were industries located along Hale’s Brook. Also known as River Meadow Brook, this stream drained nearly 24 square miles of mostly farmland, marshy areas, and woodlands in Chelmsford and Carlisle, but in Lowell its two square miles of drainage encompassed a tannery, a small railroad repair shop, several cotton waste and batting mills, and metal fabricating plants.[2] Every day, the Lowell Bleachery discharged millions of gallons of waste “liquors” from washing, bleaching, and dyeing cloth, U.S. Bunting dumped 300,000 gallons of wastewater from scouring wool, washing cloth, and dyeing stock, and U.S. Cartridge released 60,000 gallons of oil-heavy wash water from shell production.[3] In addition to the long-term problems associated with the introduction of toxic materials into the brook and in the soil within the stream’s basin, industrial dumping of wastes often had immediately destructive consequences. For example, in the summer of 1880 residents near the dam by Gorham Street decried the horrific stench from thousands of dead fish, mostly perch and pickerel, floating on the surface of the brook. As one report noted, the fish were likely killed “by some poisonous chemical which [was] thrown into the water from the soda factory or some other establishment on the stream above that point.”[4] On the river itself, textile production at the Waterhead, Bay State, Belvidere, and Sterling Mills, on Centennial Island, as well as the woolen mills and White Brothers tannery farther down stream, daily generated nearly a million gallons of scouring, washing, dyeing, and curing wastewater as well. [5] In 1878, the Massachusetts General Court had passed a law prohibiting industrial and municipal discharge of refuse or any “polluting substances” into any stream or public pond in the state, but it bowed to corporate pressure and exempted the Connecticut and Merrimack Rivers as well as the Concord within the city limits of Lowell.

Household Pollution Adding to the industrial pollution of the river was a growing amount of household waste and run-off from city streets. A number of small sewers of iron pipe, clay pipe, or brick- lined construction were installed in the Chapel Hill area as early as the 1850s. Many of these extended no more than a city block and drained limited sections of streets and walkways. City dwellers frequently dumped household wastes into streets and drains, while privies were occasionally cleaned by “night soilers.” By the 1880s the city council held a series of hearings on the growing problem of domestic pollution along the Concord and in the Ayer’s City section of Lowell. This led to the construction of a large intercepting sewer with outlets near the confluence of Hale’s Brook and the Concord River, at Lower Locks, and near the Middlesex dam.[6] Sanitary engineers believed that dumping wastes into a rapidly flowing stream, such as the Concord, was the most effective way of dealing with raw sewage. They believed that the action of moving waters enabled a river to clean itself. Although this worked to some extent, the “self-cleaning process” proved even less successful during periods of low flow. Residents along the Concord were well aware of this problem, especially during the summer months. Chester Makij describes the practice of dye houses dumping wastes into the Concord River.

The State Responds In the early 1900s, prompted by serious health problems, including occasional outbreaks of typhoid fever, as well as by complaints of foul odors and lawsuits over water pollution, the Massachusetts Board of Health carried out a series of inspections of waterways in cities throughout the Commonwealth. One of these studies centered on Hale’s Brook in Lowell. A report issued in 1917 recommended “the construction of proper sewerage facilities” to treat the wastes of factory workers in the mills along the brook as well as the industrial pollutants from these manufacturing concerns, two of the most significant sources contributing to the fouling of the brook. The report also called for an improved channel in place of the existing meandering streambed. [7] Municipal officials in Lowell partially adopted the latter recommendation, though it was hardly a solution to the unhealthful practice of dumping industrial and domestic wastes into the brook. Lowell was not alone, however, in taking such limited measures. This kind of response to pollution problems was quite common prior to the widespread (and far more costly) construction of centralized sewage treatment plants.

FOOTNOTES [2] “Special Report of the State Department of Health Relative to the Condition of Hale or River Meadow Brook in the City of Lowell,” Second Annual Report of the State Department of Health of Massachusetts, (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1917), pp. 332-336. [3] Massachusetts State Department of Health, Special Report of the State Department of Health Relative the Conditions of Hale or River Meadow Brook in the City of Lowell (1917), 5-6; Massachusetts State Board of Health, Report of the State Board of Health Upon the Sanitary Condition of the Merrimack River (1913), 28-30. [4] “A Public Nuisance,” Lowell Morning Times, July 14, 1880. [5] Massachusetts State Department of Health, Special Report, 5-6; Massachusetts State Board of Health, Report of the State Board of Health, 28-30. [6] “The Intercepting Sewer,” Lowell Morning Times, August 30, 1883, and November 14, 1883. Soon after the completion of intercepting sewers that channeled wastes from Andover, Pond, and Church streets into the Concord River, the Middlesex Company sued the City of Lowell, claiming the noxious waters infringed on its right to draw water from the stream for industrial purposes. See “Sewage in the Concord River,” Lowell Morning Times, March 3, 1885. [7] “Special Report of the State Department of Health Relative to the Condition of Hale or River Meadow Brook in the City of Lowell,” Second Annual Report of the State Department of Health of Massachusetts, (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1917), p. 335.

|