|

|

||||||

|

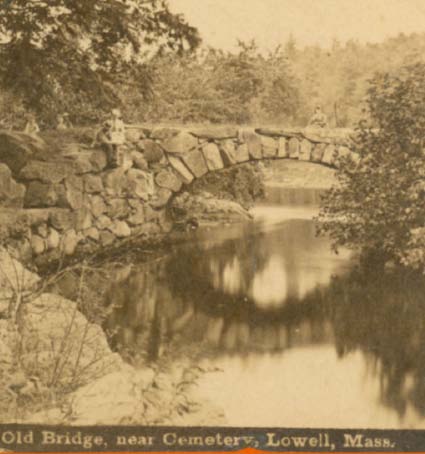

History: River for Health and Recreation Bathing in the Concord For many Lowell residents, young and old alike, the Merrimack and Concord rivers were commonly used in the summer months for bathing. Indoor plumbing was virtually non-existent prior to the 1870s, when Lowell’s first public water supply system was completed, and not until the 1880s were houses commonly constructed with flush toilets and bathtubs. For the most part, only the city’s middle and affluent classes occupied such fully furnished dwellings. The majority of workers and working-class families continued to bathe in small wash basins in their boardinghouses or tenements, and less frequently in the handful of public bathhouses in the downtown. Between June and September, many sought out the cool waters of the two rivers. Because private landowners held most of the property along the riverfronts, city residents seeking a dip in the water often found it difficult to gain access to the various swimming holes. As one local correspondent observed in 1864, “Concord River, back to a point where the mud is altogether too deep, and eels and bloodsuckers too plenty, through the week, is guarded most of the way by the vigilant and pure-minded residents of Lawrence Street, and woe to any unlucky man, boy or urchin, who presumes to expose himself in native buff within lorgnette distance of the stately rear windows of its towering mansions.” Police were frequently called to enforce ordinances forbidding nude bathing and could occasionally be seen dragging “two or three ragged urchins” to the stationhouse “to atone for the hideous crime of trying to keep cool and clean.”

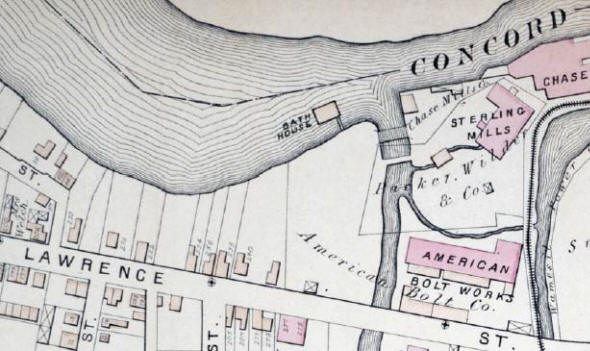

The Concord River Bathhouse In the late 1860s, a number of Lowell’s leading citizens urged the city council to establish public bathing facilities, arguing that personal hygiene was closely connected not only to improved health but also to a higher moral standing. A committee formed to investigate locations around the city selected three sites on the Merrimack River and one on the Concord River. With an appropriation of about $1,200 the four bathhouses on the Merrimack were completed and opened in the summer of 1873. The following year, the bathhouse on the Concord, located just south of the confluence with Hale’s Brook, was opened. The wood-frame structure had a slanting roof that measured 30 feet by 50 feet and a sloping and slatted wood floor to allow water in, with one end permitting a depth of two feet, while the other had a depth of four feet. Additionally, a wood platform was constructed around the perimeter of the outside walls. According to one estimate between 200 and 300 residents used the Concord River bathhouse each day, the largest number during July. The bathhouse proved so popular that the city council’s special committee arranged to have females use the facility all day Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, with men and boys bathing at other times. A policeman was assigned each day to oversee its operation, and Ann Conlan, an Irish immigrant and washerwoman, supervised on the days set aside for women. The Stirling Mills, a producer of woolen goods near the bathhouse, also opened the bathhouse early in the mornings, Monday through Saturday, prior to the commencing of factory work. This allowed its employees to bathe, and John Buchannan, about 60 years of age and a Scottish-born watchman for the woolen company, supervised the daily activity.

Swimming in Polluted Waters In the 1870s and early 1880s, the growth of the neighborhood along Hale’s Brook, and the expansion of textile production, notably dye works, along the brook and the Wamesit Canal, resulted in ever greater amounts of pollution from households and factories. Consequently, the city’s board of health recommended shutting down the Concord River bathhouse in 1882 and moving the structure to a site on the Pawtucket Canal, above the gatehouse. Lumber companies, however, used the canal for rafting logs to its sawmills and objected to this proposal. In the end, the Concord River bathhouse was simply removed, though residents continued to use the stream for bathing, swimming, and other recreational pursuits.

Theresa Marion describes winter recreation at Fort Hill Park, overlooking the Concord River.

Hear John Quealy discuss how youngsters in Lowell explored the Concord River.

|